Myofascial Trigger Points in Veterinary Patients

abridged – see link at bottom for full article.

Myofascial trigger points can be located within the belly, origin, or insertion of a muscle and are known to cause decreased changes in range of motion, muscle weakness, and postural imbalance as the patient develops gait pattern changes in order to function without pain.

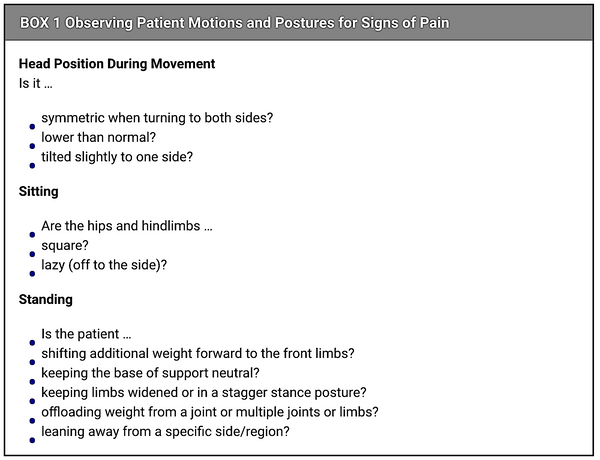

Observation of a patient’s movement and preferred postures with an understanding of abnormal movement and compensation patterns provides the first clues for identifying myofascial trigger point zones or regions in companion animals.

Appropriate therapy to reduce activation of myofascial trigger points may help veterinary patients regain normal range of motion; maintain appropriate posture, balance, and correct use of limbs (independent ambulation); and experience better, more sound sleep due to increased comfort while in the resting position.

Understanding Myofascial Trigger Points, Myofascial Pain Syndrome, and Fascia

Myofascial Trigger Points

A myofascial trigger point is defined as a hyperirritable spot or “knot” located in a taut band of a muscle, capable of producing referred pain and a local twitch response (LTR) with direct palpation or dry needling.3-5 An LTR is a spinal cord reflex and cannot be controlled; it is thought to be transmitted by central and local pathways.6 It is a rapid contraction of the taut band within the muscle belly and is evident when the myofascial trigger point is stimulated.7

In dogs and cats, the taut band is identified in the muscle belly by palpating perpendicular to the affected muscle fibers. Once the taut band is indicated, the practitioner palpates along the taut band to locate the nodule, or “knot.” A myofascial trigger point is a discrete area that feels like an intensely contracted structural unit within the muscle, or sarcomere, while adjacent muscle groups may feel supple.

Myofascial trigger points typically form after muscle injury or repetitive overuse of muscles. Persistent muscle fiber contraction can also be an adaptive response caused by low-level muscle contractions, unaccustomed eccentric contractions (e.g., lowering the weight in a biceps curl), muscle overload from shifting cranially due to hip or stifle pain, or slight postural adjustments.

For example, a dog with a digital amputation may shift weight to other body regions to compensate, which promotes changes in other muscle groups. This overload forces cellular deregulation of ions causing chronic cellular changes in specific parts of the muscles.

| VITAL VET: Want to learn Myofascial Release Techniques and Massage? | ||

|---|---|---|

| Online Course | Description | Link |

| Myofascial Release for Animals |

Myofascial Release is a safe and very effective hands-on technique that involves applying gentle sustained pressure into the myofascial connective tissue restrictions to eliminate pain and restore motion |

Myofascial Course |

| Learn Dog Massage |

A course to learn useful massage techniques you can use at home to improve well being of your dog! |

Massage Course |

Myofascial Pain Syndrome

Myofascial Pain Syndrome is associated with a type of pain within skeletal muscle and its fascia; people describe it as deep, dull, aching pain. It is diffuse and not easy to localize because Myofascial Pain Syndrome is a referred type of pain within the musculoskeletal and fascial system. Veterinary patients may display subtle alterations in gait function due to primary muscle fatigue and muscle weakness.8 They may also posture with an arched or hunched back, move stiffly in all limbs, prefer a lowered head position, and have an unidentifiable source of pain.

Fascia

The definition of fascia as it relates to myofascial trigger points is difficult as there is no consensus yet among researchers. Fascia supports, penetrates, and is distributed within body systems. It is found in bone and meningeal tissue and covers organs and skeletal muscles, creating many independent layers.9 When injured through trauma, inflammation, or stress, it can become tense and firm, altering its ability to perform its physiologic function. An observable example of fascial restriction is as follows: a patient that is stretching forward for a food lure while sitting in a sphinx position shows a ripple or twitch in the back (paraspinal muscles), then retracts back to neutral and shifts forward by rising or crawling instead of stretching further. The stretch induces discomfort, so the patient chooses to move its entire body forward and compensate to avoid pain (FIGURE 1).

Discovering Myofascial Trigger Points

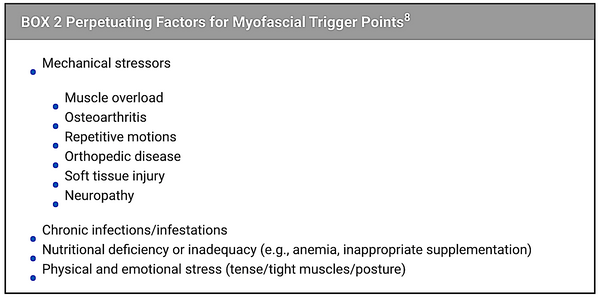

During a rehabilitation evaluation, it is common for practitioners to evaluate the patient’s posture and movement before physical palpation. When asking for a simple command such as “sit,” attention is paid to a few key responses, posture, and behavior in performing the task (BOX 1 and FIGURE 2). When findings are abnormal, such as in compensatory movements during the stand-to-sit posture, an important consideration is the history of the patient back to the earliest time their handler or owner can remember. “Did they always sit off to the side? Did they ever sit with straight posture?” myofascail trigger points create a posture imbalance or shift due to pain and are perpetuated by mechanical stressors, including underlying disease processes (BOX 2).

Although history and observation are important factors during an evaluation, palpation skill and technique are considered to be the most important tools in identifying myofascial trigger points. Understanding how a “normal” muscle feels and knowing the anatomy of muscles, including their origins, insertions and actions, are critical in discovering and treating the cause of muscle dysfunction.

Therapy

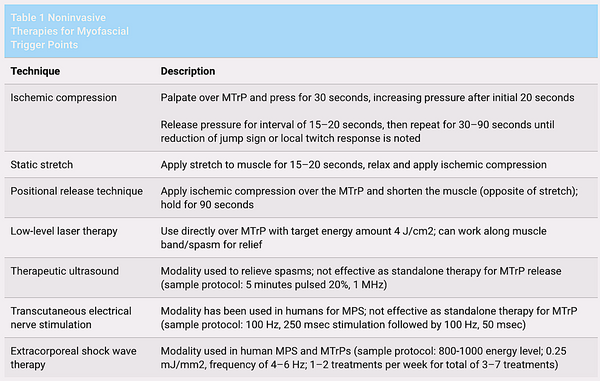

There are invasive and noninvasive therapies for the treatment of myofascial trigger points. Invasive therapy with the use of acupuncture needles or injections is considered the most effective way of decreasing and preventing recurrence in activation of myofascial trigger points. Veterinary technicians and nurses are not permitted to perform needling techniques; therefore, the therapies discussed below are noninvasive techniques that involve manual modalities and laser therapy (TABLE 1).

Manual Myofascial Trigger Point Release

Human massage therapy often describes relieving muscle “knots” by applying pressure. This is known as ischemic compression. One study has suggested that using this type of technique in myofascial therapy may be effective in reducing symptoms of human patients with chronic shoulder pain.12 In ischemic compression, the index and middle fingers are held over the myofascial trigger points for 30, 60, or 90 seconds with increased pressure after the initial 20 seconds.

To relieve muscle spasms, static stretch can be applied while performing manual myofascial trigger points release. A strain and counterstrain theory, previously known as positional release technique (PRT), was developed in 1981. This technique resets the muscle spindle, allowing the spasm to relax, by moving the joint and muscle away from the motion restriction.11

Low-Level Laser Therapy

Low-level laser therapy (LLLT) uses class IIIa and IIIb lasers, which provide a power output of less than half of a watt (500 mW). The laser applicator can be held directly over the myofascial trigger point region at a target energy delivery of 4 J/cm2, with the dose range between 1.5 and 5 J/cm2.11

A comparison study of dry needling and laser therapy in the masseter muscle found similar outcomes, with a statistical significance of reduction of myofascial trigger points with laser therapy at a dose of 4 J/cm2 or dry needling with 2% lidocaine injection over the myofascial trigger points.13 Patients were evaluated after a total of 4 sessions at intervals ranging between 48 and 72 hours; however, the number of treatments needed to deactivate myofascial trigger points varies from patient to patient depending on whether the issue is chronic or acute.

Another comparison study concluded that LLLT was more effective than dry needling; however, it stated that more studies with appropriate LLLT use and experienced practitioners are needed to prove greater efficacy. This study mentioned that LLLT may be effective at 2 to 5 treatments per week. It also suggested using more frequent treatments with higher energy for acute cases (e.g., 24 J/cm2 5 times a week) and less frequent treatments with lower energy over more sessions for chronic cases (e.g., 4 J/cm2, 2 times a week for 30 sessions).14

Therapeutic Exercise

Although exercise techniques may not deactivate myofascial trigger points on their own, exercise is helpful in activating appropriate muscles, improving posture, and decreasing compensatory issues that may be perpetuating and precipitating factors of myofascial trigger points. To help condition muscles for postural control, owners can be taught a simple “stack stance” to help their pet stand square and evenly balanced with its head in neutral position without weight shifting for a certain period of time. Gait reeducation is also helpful and can be facilitated by the use of land or underwater treadmills, obstacle courses, and curbs. It is critical during gait reeducation for the patient to demonstrate normal gait patterns such as walking or trotting and not ambling or pacing, which are common compensatory strategies.

Adjunctive Therapy

Other modalities used in veterinary medicine, including therapeutic ultrasound, electrical muscle stimulation, and extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT), may aid in reducing pain and discomfort before release of myofascial trigger points; however, they are not typically used as standalone treatment options. A few studies have demonstrated reduction of Myofascial Pain Syndrome with ESWT in humans, but veterinary studies will need to be completed to provide further guidance for practitioners.

Conclusion

A veterinary nurse’s goal is to teach clients tools to promote reduction in myofascial trigger point activation in their pets, thereby relieving pain and providing better outcomes and successful, long-lasting treatments. More in-depth articles, book chapters, videos, and coursework on myofascial trigger points in companion animals are available for readers who want to learn more about myofascial trigger points and Myofascial Pain Syndrome.

Author: Lis Conarton

Link: https://todaysveterinarynurse.com/articles/myofascial-trigger-points-in-veterinary-patients/ with references