If you’re in dog sports, chances are you know someone whose dog has suffered CCL injury. Have you ever found yourself asking how a CCL injury occurs and how you can make every best attempt to prevent your dog from suffering this injury?

In this blog, we take a deep dive into CCL injuries, how they occur, what to look out for, and how a CCL injury does not mean the end of your dog’s sporting career.

What is the Cranial Cruciate Ligament?

There are five main ligaments that support the knee joint.

- The patella ligament, which is extracapsular (meaning it is outside of the joint capsule and can be palpated and manipulated). You can read more about injuries to the patella ligament here.

- The medial ligament which resists outward turning of the knee.

- The lateral ligament which resists inward turning of the knee.

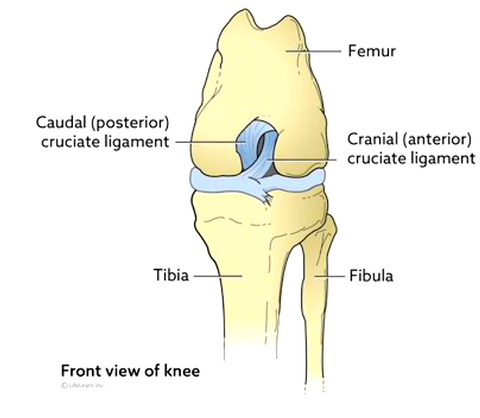

- The cranial and caudal ligament. These two ligaments are bands of fibrous tissue located within each stifle (knee) joint. They join the femur and tibia so that the knee can work as a hinge joint. Cruciate, meaning “to cross over” or “form a cross” plays a key role in ensuring the knee works as a stable hinged joint. Unlike the patella ligament, the cruciate ligaments cannot be seen or felt. The cranial ligament is responsible for the forward stability of the tibia and is the most often torn or severed. The caudal ligament, which is slightly thicker and longer than the cranial ligament is responsible for the backward stability of the tibia.

Another important structure to consider is the two meniscal cartilages of the knee joint. These two C shaped fibrocartilages are found between the articulating surfaces of the femur and tibia. It serves many important functions in the joint such as shock absorption proprioception and load bearing and is frequently damaged when the CCL is injured. In fact, meniscal damage occurs in 40% to 60% of dogs with naturally occurring rupture of the CCL ligament (Franklin et al., 2010).

How do CCL injuries occur?

Let’s dive a bit deeper into the possible causes of a CCL injury:

- Hyperextension and internal rotation of the knee – In hyperextension, the knee joint bends the wrong way, and the knee is forced to extend beyond its normal range of motion. The vast majority of CCL injuries in sporting dogs are a result of hyperextension of the knee joint.

- Sudden directional changes at speed – When our dogs make a turn the majority of their body weight is placed onto the knee and excessive rotational and shearing forces are placed on the cruciate ligaments. Something as simple as a misstep can put a little extra force onto the joint and ligament and cause a rupture.

- Jumping – When our dogs are taking off and landing a jump, they’re placing increased stress on their joints and soft tissues (muscles, ligaments and tendons). This increased strain without proper conditioning for the physical activity they are partaking in can result in injury.

- Overweight – Obese dogs appear to be more predisposed to developing a cruciate rupture. Remember that the knee of our dog bears a lot of weight and the CCL plays a crucial role in managing that weight. A dog carrying extra weight is putting increased pressure onto the ligaments and increases the risk of injury.

- Weekend warrior syndrome – If your dog isn’t ready to manage the physical challenges of an activity, you’re risking an injury. Weekend warriors can be defined as a dog that spends the majority of their time lazing about the home who on the weekend hits the hiking trails for a strenuous 6-hour hike. Placing too much strain on a limb and ligaments that are inadequately prepared for the activity can result in an CCL injury.

- Repetitive normal activities – A big area where I see CCLs occur in pet dogs is from a round of fetch. Often times owners are throwing a ball with little regard to the amount of work and effort their dog is putting into retrieving the toy. The dog is also engaging in an activity with speed and could be making quick and sudden turns to retrieve the ball. Fetching is also an activity that owners tend to do often and to fatigue which results in further stress on the ligaments.

- Degeneration of injury – If there is an existing injury that isn’t fully rehabbed or an old injury with scar tissue that’s creating more immobility this can put additional stress on the knee joint structures and neighboring tissues.

- Excessive loading from contralateral lameness – Compensation from lameness of a different leg can put more strain on the other health limbs. Research has shown that there is a 50-60% chance that in the first year your dog will injure the CCL on the other leg.

- Conformation abnormalities – Some dogs are just born with structural challenges that could predispose them to an injury of the cruciate ligament. A dog born with luxating patella or a dog with hip dysplasia is at a higher risk of CCL injury so recognizing that our dog’s body may predispose them to an injury is an important part in injury prevention.

- Breed propensity – Some breeds are more prone to CCL injuries such as Labrador Retrievers, Newfoundlands, German Shepherds, Rottweilers, and Golden Retrievers.

- Early spay/neuter – Research has shown that dogs that are altered at a young age (under 12 months) are at an increased risk of CCL injury. The incidence of CCL in the early alteration of the dogs in the study was 5.1 percent in males and 7.7 percent in females (Hart 2020).

Signs and Symptoms of CCL Injuries

- Lameness or limping in the hind end.

- Difficulty with transfers (e.g. sit/down).

- Toe touching – does not bear weight properly on the affected leg but will just touch the toes to the ground.

- Pain in the knee region.

- Sloppy sitting posture (i.e. one leg splayed out).

- Decreased hind limb circumference – muscle loss in one limb.

- Stifle effusion (swelling).

- Lameness that is worse with activities.

- Lessened desire to play.

- Gait (observe in walking/trotting/circles). Dogs will tend to lean away from the affected limb. Sometimes, lameness is only seen in the faster trotting gait versus a slower walk.

How to Determine if your dog has a CCL injury?

During the assessment, the following will be evaluated:

- The circumference of their hind end muscles to determine if there is any muscle loss/atrophy. A greater difference in muscle mass between unaffected and affected leg is often a sign that the injury has been going on for a while and likely not acute.

- The current range of motion (ROM) of the affected knee.

- The weight bearing status of your dog commonly assessed with a Stance Analyzer or gait analysis machine. Objective numbers help to obtain an accurate baseline from which you can measure your rehabilitation success.

- Knee swelling, which can be detected by both palpation and knee measurements.

- Front assembly, spine and unaffected leg (ROM, flexibility, pain) to determine other areas of strain or compensation (e.g. excessive loading on the front end).

-

The integrity of the CCL via special palpation techniques.

There are different tests that can be performed by your health professional to determine if your dog has knee joint instability.

The Cranial Drawer Test – one hand stabilizes your dog’s femur while manipulating/moving the tibia with the other. If the tibia moves forward, known as a positive drawer because of the way the bone moves similar to a drawer being opened, the ligament is ruptured. In the videos below you can see my client’s Australian Shepherd Lily have a drawer test performed on both her knees.

Cranial Tibia Thrust – Stabilize the dog’s femur with one hand, while flexing the ankle with the other. In dogs with a ruptured cranial cruciate ligament, the tibia will display forward motion upon flexion of the ankle joint.

It is possible for a dog to show a false negative from these tests if they are quite painful and guarding their knee. In these cases, radiographs can help in confirming the diagnosis. Radiographs can also help confirm the presence of joint effusion/swelling which indicates a problem within the joint.

How is CCL treated?

It is important to consider that not all dogs are surgical candidates. Some dogs may not be good surgical candidates due to:

- Age

- Weight

- Breed issues

- Poor health

- An inadequate state of fitness

- Financial constraints, or owners’ beliefs

- Or they look pretty great functionally despite injuring their cruciate ligament

Treatment options will also vary depending on your dog’s lifestyle and their sporting/activity goals. Whatever route you take, the rehabilitation process plays a huge role for getting your dog back to their normal activities. Research has shown that dogs who participated in rehabilitative therapy post-CCL injury return to normal activity quicker than dogs who did not (Marsolais 2002).

The goals for rehabilitation should globally be focused on: reducing pain, promoting healing, building muscle mass and promoting muscular development, joint stability, body awareness and flexibility. The focus should be on a return to function, prevention/delay of degeneration of joint disease (e.g. arthritis) and improving overall health and fitness.

Rehabbing the Sporting Dog with CCL

The sporting dog with a CCL injury is very different from the pet dog with a CCL injury and should be treated as such. For sporting dogs, I recommend a much more intense and longer rehab approach as these dogs are working towards a return to sport and will face greater physical demands on their body in the future. Whether a dog is coming for post-operative rehab or conservative management of their CCL injury, our first goal is to complete a thorough assessment of the dog to determine their baseline function and build a plan for their rehabilitation process. The goals of this stage include focusing on increasing ROM, increase muscle function and weight bearing, improving proprioception and decreasing pain and joint swelling. An important mantra to keep in mind is that “movement is medicine,” and we want to ensure our dogs keep moving in a way that is appropriate for their stage of healing and recovery. Crate rest is a thing of the past!!! Research has shown that dogs placed on strict crate rest post-TPLO were 2.9 times more likely be categorized as having an unacceptable function at 8 weeks than dogs who participated in a supervised physical rehabilitation program (Romano 2015).

Rushing headlong into exercise without careful consideration of our dog’s current physical ability will only risk further injury or slow the healing process. During this initial and crucial stage, lifestyle management is always discussed. This includes a review of the dog’s home environment (e.g. increase carpets and mats to prevent slipping, no access to stairs) and discussions around factors that can cause re-injury to either the affected or unaffected limb (e.g. jumping, rough play with other dogs, longer walks on uneven terrain, twisting motions).

As your dog progresses through their rehabilitation journey a variety of techniques may be used by your rehabilitation provider to speed and support tissue healing and function. These techniques could include: manual therapy (e.g. soft tissue massage, myofascial release, cross friction massage, joint mobilizations), modalities (e.g. laser, PEMF, EMS, Assisi loop) and gradual/progressive exercise program to maximize ROM, weight bearing, strength, flexibility, and body awareness.

The return to functional activities (e.g. longer leash walks, proper positioning with sits/downs and navigating stairs) will depend largely on the individual dog’s stage of healing and recovery. Progressive exercises will begin to be introduced – these exercises look to make sure our recovering dog is ready to meet the demands of life. Our goals at this stage is to ensure that limb circumference is symmetrical (remember that it’s not uncommon to see a size difference between limbs with a CCL injury), gait has returned to normal, and that the surgical limb (if post-op) is fully healed.

A common question I get asked is when should I be progressing my dog’s exercises?

Once muscles fall into a comfort zone and workouts are no longer challenging the body begins to plateau and stops building muscle. This signifies that it’s time to begin increasing the challenge to our dogs. Unchallenged muscles can also begin to degrade; limiting your dog’s recovery. To continue challenging our dog’s healing tissue we need to add other demands to the musculoskeletal system. This continues to build muscle and allows us to see if the existing injury will reappear with increased demands. There are several ways we can add challenge to a workout:

- Strength – Increasing the amount of load applied to the tissues. Also specific to range of motion.

- Endurance – By increasing the reps we ask our dogs to perform. How long the tissues can maintain that load. Both a factor of cardiorespiratory endurance and muscular endurance.

- Speed – Increasing the speed of an exercise.

- Power – A combination of strength and speed. Power exercises are called plyometrics

- Equipment changes (both stable and unstable).

The final stage of the rehabilitation process is the “Return to Sport” phase which generally begins around the 14-16 ++ weeks. In the beginning of your dog’s CCL injury, it may not feel like a return to sport is even possible!! However, studies have shown that dogs with CCL injuries who received TPLO surgery were able to return back to their pre-injury level of competition without further injury (Heidorn 2018). Despite the long road to recovery, a return to sport is possible!

Is there always a chance of another potential injury? Perhaps, but this is the risk of playing dog sports, or any sport for that matter! However, if your dog has successfully completed a progressive and high-level conditioning program geared to mimic the movements seen in your dog sport, you are setting up your dog for success. At this stage, we stress your dog’s body to prepare them for a return to sport and constantly evaluate how their bodies are handling the increase in demands. This can be fine-tuned and tailored throughout the rehabilitation process. Setbacks are expected in the rehabilitation process but can help give valuable information to owners and their rehab team on the dog’s readiness to return to sport. We do this so that by the time you get back to the performance ring you have the peace of mind and confidence in knowing your dog’s injury has fully healed and can meet the demands of their sport.

The focus on return to sports should include elite level conditioning exercises for strength and balance, jumping exercises, sport specific training, quick directional changes/pivots, interval training, sprints, power/plyometric focused exercises and cardiovascular endurance.

Once your dog has graduated from their return to sport program, owners will continue to have regular follow-ups with their canine PT to ensure that their dog is continuing to improve and is not showing early signs of a potential issue. It is likely that a dog with a CCL injury will still develop arthritis later in life. However, by keeping up with a conditioning program post-injury you’ll better prepare your dog for this challenge and delay the onset.

A CCL injury can take almost a year to heal. A study of agility dog with CCL tears treated with a TPLO surgery found that average time for a return to sport post-surgery was 7.5 months (Heidorn 2018). The other risk in recovery is that many dogs with a CCL injury will rupture the CCL in the other leg (statistics tell us that 40-60% of the dogs).

Another option to aid in the healing process and manage the injury is the use of a stifle orthotic (knee brace). Braces are a popular management tool for dogs with CCL injuries. Research has shown that braces help with proprioception and joint position sense, reduces fatigue and permits the injured limb to relax (Canapp, 2018). A study also found that there was a 3% difference in weight bearing when the dog was wearing a knee brace suggesting that a custom canine stifle orthotic allows for improved weight bearing in dogs with unilateral CCL tear (Carr 2016). If you choose to have your dog wear a brace it’s crucial that you make sure the brace is properly fitted to your dog. This is where your rehab team can help! Bracing may also not be a good option for dogs with a torn meniscus as the compressive forces of the knee still cause quite a bit of pain for the meniscus. Remember, when using a brace watch for potential complication such as: persistent lameness, skin lesions, and intolerance. If you would like more information on bracing, I recommend OrthoPets.

Injury Prevention

There are a couple key things we can do NOW to prevent CCL injuries in our sport:

- Warm up and cool down our dogs before and after activity. I’m a huge advocate for this incredibly simple yet powerful thing we can do to prevent injury. Warm ups help prime our dog’s muscles for strenuous activity.

- Weight management – Keeping our dogs at a healthy weight can make a huge difference. Carrying extra weight adds undue strain to the knee joint and increases the risk of injury.

- Routine conditioning program – a weekly conditioning program can go a long way to preventing injury. Conditioning programs help to keep muscles strong and flexible so that they can properly support the joints and body.

- Routine flexibility program – Incorporating flexibility exercises into your regular conditioning work ensures muscles stay at the proper length for the activities they do. Unused or unchallenged muscles become short and inflexible generating less power and can lead to extra pressure and forces on neighboring tissues.

- Rest days – The benefits of exercise don’t occur during our workout sessions but rather during our rest periods! Exercise causes tiny tears in the muscles (this is normal). Rest days allow the body and muscles to repair and adapt to become stronger.

- Choosing smart and safe activities –some activities have a higher level of risk for an injury than others and you may be surprised to learn that playing fetch / ball throwing is the #1 cause for CCL injury in dogs entering my clinic. Although dogs tend to love the game of fetch, not all dogs are suitable for this activity based on how their body contorts during the actual retrieval part of the activity.

- Routine health assessments with your health professional to identify early issues, areas of compensation, tightness or pain.

- Nutraceuticals & natural anti-inflammatories – please see article for recommendations.

The risks of an active lifestyle far outweigh the risk of injury and we can’t bubble wrap our dogs. Injuries do and will happen but by taking preventative measure we minimize the risk of injury and improve our dog’s rehab prognostics when an injury does occur. Make sure to pay attention to your dog’s subtle changes. Your dog’s posture, positioning, mannerism, reluctance to turn, and offloading are all warning signs that if we catch early can drastically change the outcome of their prognosis!

A final word…

Having a support system around you can greatly help in the recovery process by giving you the tools to help support your dog in the rehabilitation path you have chosen. If your dog has been diagnosed with CCL or if you would like to introduce your dog to a conditioning program to help prevent a future injury please don’t hesitate to reach out to me about building a program and treatment plan!

Author: Carolyn McIntyre

Link and References: http://www.mcrehabilitation.com/blog/condition-breakdown-cranial-cruciate-ligament-injuries